In This SectionClick on the links below to go to each specific section. After clicking on a link, you will see the section at the top of the screen.

What was the Voting Procedure? What was it like in the chamber? Foreign Policy, Security, and Diplomacy |

One of the Oldest Parliaments

Meetings of the old Scottish parliament were not always called ‘parliaments’. There is much confusion between the terms parliament, council, general council and convention of estates and it is possible that those councils we know of from as early as the 12th century reign of David I were essentially parliaments. So far the earliest record of the Latin term ‘parliamentum’ is 1265 and if we take the term ‘colloquium’ to be synonymous with parliament then we can go back even further to 1235 and a letter of Alexander II at a colloquium at Kirkliston near Edinburgh. Certainly, Scotland’s parliament was very old by 1707 and as old as that of England which dates back to the reign of Henry III and the 13th century.

What was the Parliament?

The parliament of Scotland was unicameral, that is it consisted of one chamber. As with the old parliament so with the new Edinburgh parliament first convened in 1999. Parliaments met as ‘the estates of this ancient kingdom’ summoned by the crown on 40 days notice. An alternative gathering of the ‘estates’ was the convention which met at shorter notice, was generally though not always a smaller gathering, and had less legislative and judicial authority. In parliament or convention there were three or four estates and through the attendance of the estates we can see that the Scottish parliament evolved as a body.

Almost always the clergy, the first estate, was present before and after the Protestant Reformation of 1560, though not from 1639 to 1651, and after they were restored in 1661 they finally vanished from parliament in 1689.

Always present were the second estate, the nobles and lords as tenants-in-chief, although in the mid-fifteenth century, when lords of parliament (or parliamentary peers to use the British term) were introduced, who was under a special obligation to attend, lesser or small tenants or lairds stopped attending parliament, other than those who were officers of state attending ex officio. The original right of all tenants-in-chief to attend was simply forgotten and the reforms of 15th century were really to clear out the lairds.

Nonetheless, King James I had proposed in the early fifteenth century that lairds be accommodated by representative means, though it was only following the County Franchise Act of 1587 that a new (fourth) estate, commissioners for shires, was introduced and with them shire elections. Those tenants-in-chief whose lands were assessed at forty shillings annual value, under what was known as the Old Extent, that is an old land assessment, had the franchise and could vote and stand for election. The size of the electorate per shire remained small ranging from 20 to 100 voters only. Each shire had 2 commissioners but only one vote, though the smallest such as Clachmannan and Kinross had only 1 commissioner. However, in the constitutional arrangements put in place by the Covenanting regime in 1640, the removal of the clerical estate was compensated for by allowing each shire commissioner a separate vote, a doubling of the shire vote that was continued after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660. In the parliaments of 1661 and 1681 there were further refinements to the property qualifications that extended the franchise, and the 1681 act also required the electoral roll to be revised annually. This reform was the final adjustment to the franchise until 1832! Finally, in 1690, shire representation was increased when some larger shires were permitted three or four commissioners depending on their size and from 1693 to 1707 the maximum shire representation stood at 92 commissioners. However, in spite of some healthy electioneering, in reality the influence of the local noble magnate and the crown remained strong over the electoral process.

The last and third traditional estate was the burghs, first appearing in the 14th century but in and out before becoming a regular feature by the end of the 15th century. The burgh commissioners were representatives of the royal burghs and were nominated or elected by their respective town councils who in turn elected their successors. This allowed noble and family domination of the councils, for example by the Menzies family who dominated Aberdeen from the 1440s to 1630s. Burgh attendance was seen as a practical means to legitimise taxation. There were, however, various types of burghs. Royal burghs had the crown as their superior but baronial burghs (where the superior was a baron or noble) and ecclesiastical burghs (where the superior was a senior cleric, often a bishop) were not represented in this way although their superior usually sat in parliament in any case.

As we enter the busy last 18 years of the parliament after 1689 we revert back to 3 estates, nobles, shires and burghs plus the officers of state, this last group limited to eight persons in 1617, the most common attendees being the Chancellor; the Privy Seal; the Lord Advocate; the Clerk Register and the Justice Clerk. Officers of state voted in their respective estates but like the clergy there was considerable jealousy about the dangers of too much voting power being given to cronies of the crown. This partially explains why officers of state were excluded from parliament 1640-51 and why the number who could vote was limited in 1617.

How Representative was it?

We are a bit obsessive in the modern period about ideas of true representation and true democracy. Clearly what occurred in the Scottish parliament before 1707 was not ‘indirect rule by the majority of a universal of electorate’, but on the other hand it was not as unrepresentative as it might at first appear.

Members of parliament (they were not known in any official or general way as ‘MPs’) were not members of distinct political parties as we know them today, although the politics of groups or parties began to emerge from the 1660s and there were some heavily contested elections between those in power (the court) and those out of power (the country). Therefore members attended as representatives of their estate and sat in the chamber by estate not by party grouping.

Nobles and clergy attended by right of summons and officers of state as crown nominees. The burgh and shire commissioners were elected, and there was competition for seats as seen in the numerous election disputes, or controverted elections, which arose after 1639. Disputes arose as to whether individuals, candidates and electors, had signed religious test acts and oaths of allegiance, where the vote was a tie and whether members of the electorate met the franchise rules relating to wealth and residency, even though the latter was sometimes ignored. Until 1669 the whole house looked at disputed elections but from then until 1689 it fell to a nominated committee for controverted elections as the government set about controlling election disputes for political purposes. It is worth noting that this manipulation was as common before and after 1689, although after 1689 the whole house elected a committee rather than the estates choosing members separately, and from 1703 to 1707 election problems were considered before the whole parliament.

However, perhaps more important is the basis in which the members in the Scottish parliament represented their localities, shire, burghs, regional earldoms and landed estates. The link with parliament was always land and even the burghs were corporate tenants-in-chief. Nonetheless, as very few challenged the right of the landed interest to represent the country before 1707, land was in a ‘best worst’ position to represent the interests of the tenant farmers, craftsmen, fishermen and general populace. When a Fifeshire laird sought to use parliament to protect his interests in coal and salt he may indirectly have represented the interests of his coal and salt workers.

Nonetheless, this could be a small assembly and also attendance was very variable. From 1603 to 1660 its membership exceeded 150 on only six occasions and never rose above 183. After the Restoration it only twice exceeded 190 until 1703-6 when it averaged 226 with on, on average, 67 nobles, 80 shires members, 67 constituent burghs and the remainder being officers of state. In 1641 only 29 attended! In a Scottish feature not found in England, by the 1690s as many as 50 additional, extra-ordinary individuals and assistants attended who were invited to advise though never to vote. Also, elections were infrequent, and from 1689 to 1707 there were only two general elections in 1689 and 1702.

Where and when did it meet?

From the mediaeval period parliament met in a variety of places – Perth, Stirling, Holyrood and various other royal centres, sometimes in a church, a palace or a castle. Parliament followed the King in other words. It was only from the reign of James II that Edinburgh became increasingly the home of parliament and when in Edinburgh it mostly met at the Tolbooth (town council building) near St. Giles Cathedral, or in St Giles itself, though James VI was fond of gathering at Holyrood. The completion of the Parliament House in 1639 at last gave the assembly a permanent home, even though the Covenanters moved around a bit in the 1640s. For example, the session of parliament in 1645-6 moved to St Andrews to avoid the plague that ravaged Edinburgh. [For illustrations of Tolbooth and Parliament House, see Workshop seven, nos. 2, 3 and 4.]

Parliament or conventions did not take place every year and nor did they occur in particular months. While the months March to October were the most common they met at any time, and sometimes for just a few days. Parliament met most regularly not after 1660 but after 1689. In essence parliament met when the court required something, taxation for the court or for military expenditure and security, a new religious policy, or the confirmation of a new regime or monarch. If we take the period 1660 to 1707 parliament met on average for 40 days every year but not at all in, for example, 1664, 1668, 1675-7, 1679-80, and 1687-8. Also, after the collapse of the Covenanting regime in 1651, parliament was suspended until 1660, although for a brief period from 1657 the Cromwellian regime introduced a type of parliamentary union where Scottish representatives went to London. Nevertheless, with the exceptions of some periods, such as the last decade of the reign of James IV (d.1513), the estates gathered fairly regularly.

How did it work?

In Scotland the king or queen attended Parliament, sitting on the throne and therefore sitting among the members, as did Queen Elizabeth II in 1999 and at the subsequent state opening of the new devolved parliament in Edinburgh. The monarch contributed to the debate and some like James I and VI suffered from a degree of verbal diarrhea. After 1603, when the monarch resided mostly in London, a High Commissioner, or viceroy, sat on the throne representing the crown with instructions on key legislation and power to give royal assent to the process of touching the royal sceptre against a final copy of the legislation, not with royal signature as at Westminster and Edinburgh today.

(Click on Link for PDF of Image)

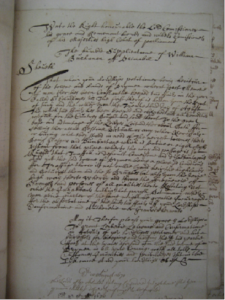

[The image of the parliamentary register above shows William Douglas, Duke of Queensberry to be the royal commissioner for James VII at the Parliament of 1685. (NAS. PA2/32, f.146-146v. Reproduce courtesy of the National Records of Scotland). [RPS, 1685/4/3]]

Who was the speaker or lord chancellor? In fact, there was no actual speaker, in spite of the occasional use of the word, and instead, a president was appointed, normally the chancellor (a noble and occasionally a cleric) when he attended.

Business was carried out in 3 ways:

- By the whole house (sometimes a committee was the whole house)

- By debate in estate (especially from the 1590s to 1630s)

- By committee (with generally equal representation from each estate)

Committees and commissions existed in the 14th century but developed more complex character by the seventeenth. The constitution of the Covenanting period (1639-51) introduced various ad hoc and standing committees and some of this approach carried on into the Restoration period (1660-89) when standing committees were established for trade, controverted elections and for the security of the kingdom. However, after 1702 matters tended to be considered in plain (or whole) parliament as members were suspicious that the crown was packing committees with cronies.

The most important committee in the history of the parliament was the Lords of the Articles, established by the 1460s and continuing until 1689 bar the years 1640 to 1661, and consisting of members chosen of each estate. The power of this committee is one of the controversies exercising Scottish historians, and there is no space here to go into the debate. It is true that the committee took over the drafting, preparation and scrutiny of legislation for much of the period, parliament gathering to choose the Articles departing to the inns of Edinburgh and returning at the end of a session to vote legislation through en bloc, perhaps in a single day. However, there was actually much to and fro between the Articles and other MPs and it was large committee, in the 17th century around 40 strong and so larger that some full parliaments held when it was abolished in the 1640s. Also, the Articles did answer to full parliament and periodical reporting after 1660, rather than en bloc reporting allowed more opportunity for voting. The crux of the matter is how much you believe the crown was able to control membership of this committee. Clearly though, its abolition in 1690 made crown control of parliamentary business more difficult and helped encourage the growth of party politics before 1707.

For a discussion of the Lords of the Articles and procedures generally see A.J. Mann, ‘House Rules: Parliamentary Procedure’ in K.M. Brown and A.R. MacDonald (eds.), The History of the Scottish Parliament volume 3: Parliament in Context, 1235-1707 (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2010), 122-56

(Click on Link for PDF of Image)

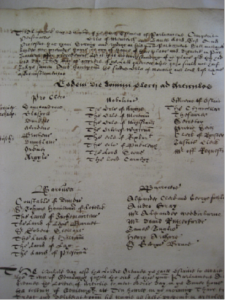

[See above: this page from the registers of parliament shows the composition of the committee the Lords of the Articles as constituted for the parliament of 1621. Note the five groups: clergy, nobles, burghs, shires, and officers of state. (NAS. PA2/20 f.5r. Reproduced courtesy of the National Records of Scotland). [RPS, 1621/6/9] ]

What was the voting procedure?

Until the mid-seventeenth century the deliberative and voting possibilities for individual members were somewhat limited. There was choosing the Articles of course, though the selection from burghs and shires was sometimes left to the nobles and clergy, who chose each other, and not with the burgh and shire estates themselves. Voting the acts en bloc at the end of a session could make it impossible to vote on a single act. This could, however, put some pressure on the government where vital taxation legislation might be blocked if Parliament was unhappy with say a toleration or religious question. However, after 1689 voting was possible on a more regular basis and proceeded act by act. Voting was oral, not by secret ballot or by lobby. The roll was simply read and members voted ‘aye’ or ‘no’ and indeed the practise of recording voting lists did not become common until 1701. From the mid-1690s rules were introduced such that no act could pass in one sitting and also second readings became the norm.

What rituals were used?

Ritual is and was a vital part of the culture of parliaments and assemblies in any kingdom or country. We know only a little of the Scottish parliament’s internal rituals, though we have hints. Members sat wearing their hats, and according to an act of 1641 those who could not vote but attended were expected to sit uncovered, though we do not know if members removed their hats to speak as occurred in the House of Commons. By 1641 we have a detailed indication of daily routine. There were two sessions every day, one from 9 o’clock until 12.00 (just like the English Lords and Commons) and another from 3 o’clock until 6 o’clock, except on Mondays (a free day) and on Saturdays where there was a morning session only. A ‘great bell’ was rung to call members to meet at the start of each day and a ‘little bell’ rung to mark the hour of dissolving. Nonetheless, the most dramatic ritual was the ‘riding’ of parliament which occurred at the start and end of each parliament though not each session. Thus although there were ten sessions under King William, in a single parliament stretching from 1689 to 1702, there were not 10 ridings. Indeed parliament was prorogued in 1707 no doubt because a last ‘riding’ would have been a focus for popular protest and riot against the union of the English and Scottish parliaments.

In 1606 James VI and his privy council regulated for the ‘riding’ which set out from Holyrood to the tolbooth or later the Parliament House: burgh members 2 by 2 on foot; shires 2 by 2 on horse; followed by nobles and clergy in the order Marquises and Dukes; Archbishops; Earls; Bishops and Lords, ‘ the latest in creation to march foremost’; then the ‘honours’ (crown, sceptre and sword without which no parliament could be valid) followed by the High Commissioner. Restrictions were placed on retinue, 24 for earls and 12 for lords and so on. All moved by the procession to the Parliament Close by St. Giles Cathedral and then walked to the Parliament House creating a scene of complete chaos in the narrow High Street as horses were dismounted. [For illustrations of the ‘riding’ of parliament see Workshop seven, nos. 5 and 6.]

What was it like in the chamber?

When all entered parliament they sat in their estates and the role was called before parliament was ‘fenced’ by the Lion King-at-Arms and the Clerk Register. Fencing was a declaration to exclude the unauthorised and to warn of no interference in the business of the high court of parliament. [For an illustration of the internal structure of the assembly see Workshop seven, no. 7]

We are not able to be precise about the internal layout but five plans have been developed by Alastair Mann [See link to PDF here] which us give some idea. The only visual guide, that provided by de Gueudeville’s illustration printed in the 1720s from second-hand information (see workshop 7) (the basis of plan 4), we know to have inaccuracies. For example, it does not include a table for the lords of session provided at least since 1662. The orientation to the throne has led to much confusion: the plans presented assume the view from the throne. Surviving sources use undefined terms which muddy the waters: ‘lesser’, ‘greater’, ‘senior’ ‘first and second degree’ when it comes to barons or nobles. We know for certain however that the seating was organised with senior individuals located separately from junior, as is clearly the case from 1689 when nobles sat both left and right (plan 5).

Put simply, as suggested by the 1580s (plan 1), available seats were probably allocated according to the seniority used for voting until each relevant row was full. Nevertheless, other accounts than those used for these plans provide yet more variation. A draft act of 1641 (not implemented we assume so hence plan 3 being similar to plan 5) states that earls were to be to the east of the throne (located south) and Lords to the west, with shire members on benches on the earls’ side and burgh members on benches on the Lords’ side [see RPS, A1641/7/6], but tradition placed the clergy on the right-hand (east) and nobles on the left (west).

The arrangement may have changed in the 1660s. The Restoration lawyer Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh in his Memories of the Affairs of Scotland (1821), suggests seating altered in 1669 (the first session he attended), and that from 1662 to 1667 archbishops, dukes and earls sat on the ‘right’ facing bishops and lords on the ‘left’, which conforms to plan 4. A 1670s account published with an edition of Archbishop John Spottiswood’s, The History of the Church and State of Scotland (London, 1677) claims that archbishops sat ‘higher’ than the bishops, and senior Earls ‘higher’ than lords, rather than front and nearest the throne as in the 1580s. Also, it has shires commissioners on the bishops’ side which conflicts with the 1580s and 1612 descriptions (plans 1 and 2). Confused orientation to the throne accounts for some of this as does the fact that even after 1639 and the completion of a permanent parliament house, some benches were clearly re-fashioned for different sessions rather than being permanently in place

What did it actually do?

Parliament was something of a ‘universal set’ in the affairs of Scotland. We would expect this today but it was also true before 1707. Parliament was a macrocosm of Scottish life and affairs. It considered a huge variety of matters and legislated accordingly:

Judicial function

Parliament was above all a court, the highest court of the land, and there were certain judicial functions only it was had power over which distinguished it from councils or conventions, and indeed other civil and criminal courts: these included all treason and forfeiture cases and the ‘falsing of dooms’ (i.e. appeals from lower courts) though from the sixteenth century the Court of Session handled most of the civil business. Parliament still handled appeals known as ‘protestations for remeed of law’ though decisions of the session were rarely suspended and matters were often devolved to the Lords of Session.

Taxation

Before the reign of James VI the monarch was expected to live off his or her own means (that is, income from crown lands, customs, fines and forfeitures) and while early taxations were granted for this and that, Parliament also blocked efforts to raise extraordinary taxes as it did, for example, in the reigns of James I and James III. However, the tax regime became more complex in the seventeenth century with in 1621 the introduction of a regular land tax (set at 5%) which developed the character of an income tax; excise duties appearing from the 1640s; the introduction of a monthly ‘cess’ or tax on assessments of valued rent in 1667, which lasted until 1707 and, to reduce the burden on land, a poll tax from 1693 with a hearth tax in 1691 of 14 shillings per household, the last of which was quickly abandoned. Conventions of estates were called in 1665, 1667 and 1678 purely for the purposes of raising tax revenue.

(Click on Link for PDF of left-hand image)

(Click on Link for PDF of right-side image)

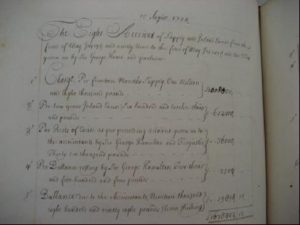

[See above: Taxation was a major part of the business of the estates. The extract (left) from the printed session record of the 1678 convention shows part of the listing of commissioners of supply who had the job of ensuring that taxation was gathered in each shire. Also (right) we see some of the taxation accounts approved by the Parliament of 1704. (NAS. PA 8/1, f.182-190 and NAS. PA2/38 f.208. Reproduced courtesy of the National Records of Scotland). [RPS, 1678/6/22 and 1704/7/89]]

Economic policy and trade

Parliament passed a variety of economic measures taking action on coinage; adjusting interest rates; passing legislation to ban imports and exports; setting rates of customs and excise; licensing manufactories and patents and setting up specialist committees to consider measures for the advancement of trade. In particular, in the Restoration period, we see extensive granting of markets and fairs throughout the land.

(Click on Link for PDF of Image)

[See above: Parliament got involved in all aspects of the life of kingdom and here we see legislation passed in 1621 controlling the stealing of hawks and hunting in winter. NAS. PA2/20, f.38v. Reproduced courtesy of the National Records of Scotland. [RPS, 1621/6/44]]

Parliaments and kings govern people and so they become involved in the social fabric and before 1707 in a somewhat ‘nanny knows best’ manner. Education at school and university, morality private and public, policies over the poor and idle, and further statutes that protected minors, inherited wealth, rights of way and that supported town authorities in a variety of initiatives to rebuild urban areas harbours and bridges after war, fire and flood are but some of the areas in which Parliament legislated.

Foreign policy, security and diplomacy

The conventions called by Charles II in 1665 and 1667 were for the purpose of raising money for the war with the Dutch and throughout the history of Parliament funds were provided for specific campaigns; security measures were passed to maintain the military fabric, castles and artillery, and after 1660 a standing army was retained until 1667 and a locally controlled militia was then formed and had to be funded. Foreign policy was at the behest of the king for the most part, although Parliament from time to time asserted its right to sanction war. The Regal Union of 1603 distanced Scotland from foreign policy even more but in as much as it concerned trade, such as with arrangements with the staple port* at Veere in the Low Countries, a port where Scots traded duty-free, it continued to be active. Also, communications with the Crown and Westminster had to be maintained. Meanwhile, internal security like the suppression, arrest and punishment of religious and political dissent remained a key parliamentary and government concern.

Religion

The religious policy was one of the cornerstones of parliamentary business. Legislation confirmed the distribution of church lands, secured stipends (salaries) for ministers and, according to the government of the day, stated the degree of royal authority over the government of the church. In the main Parliament reflected crown policy, although it was also petitioned by the clergy, especially the general assembly when it met, to legislate over issues such as incest, witchcraft, blasphemy and general immorality. Some issues such as education were areas where legislation and church interest could converge.

Ratification of crown activity

Parliament also ratified crown appointments and gifts of titles and lands and much of the business of Parliament was in the ratification of land, titles, and privileges gifted to individuals, burghs and corporations. Many gifts and patents that passed the Crown’s great and privy seals were confirmed by Parliament.

Petitions

Parliament was in receipt of many petitions, overtures, sometimes as draft acts, from both individuals and organisations. These were vetted by the Clerk Register, sometimes even by the privy council, before being submitted to Parliament. After 1689 petitions were referred to committees beforehand for consideration. The tradition of petitions to parliament has been re-introduced into the working of the new parliament established in 1999.

(Click on Link for PDF of Image)

[See above: A typical petition submitted to Parliament. In this case, in 1670 the estates responded to the petition by one William Buchanan by granting markets to the town of Drymen in Stirlingshire. (NAS. PA6/21, 22 August 1670. Reproduced courtesy of the National Records of Scotland). [RPS, A1670/7/7] ]

Background political context – party and faction

It should not be forgotten that the legislation and the evolution of the mechanisms of Parliament, of course, occurred in a political context. Factionalism has been ever-present in Scottish politics and before the union of 1707 we see the advent of party politics, although it had begun to emerge in the 1660s. Pre-union politics was not, though, party political as we know it today, of left and right but more a case of locating politics by map reference.

The following graphic illustrates how politics was structured in the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century:

(Click of Link for PDF of Image)

Click on arrow to scroll immediately to the top of the page